On July 2024 I spent long time in the Indian State of Punjab , where I had close encounters with many farmers and agriculture workers and labourers. I talked about this trip on an article published by PagineEsteri.

This blog article is intended to complement the recount of my experience among Punjabi farmers and peasants, which made me get to know various aspects about the situation of thsi sector in the State of Punjab, and the conditions of the farmers. I traveled far and wide, from farm to farm, among organic farmers that are part of the organization Kheti Virasat Mission (KVM). KVM, founded by the journalist Umendra Dutt in 2005, deals with the dissemination of organic and natural farming principles in Punjab…

Punjab has a very peculiar and unique history: during the Green Revolution during the 1960s, it was made the bread basket of India by the Central Government. This led to disproportionate agricultural development, transforming a society of mainly traditional and subsistence farmers into one of intensive, though in most cases marginal, small-land owners, practicing almost exclusively a monoculture regime with high use of chemical pesticides.

This choice has led Punjab to be one of the most polluted lands in India, with several environmental problems, including over-exploitation of groundwater, the level of which is decreasing year by year, due to paddy cultivation.

I collected stories from the many farmers I met during my tour.

Many of them changed their crops from “industrial” to organic or natural because of dramatic personal events, as in the case of Swarn Singh, who converted his crops to organic in the early 2000s following the death of his wife from cancer due to high pesticide use in the fields.

Harteh Singh Metha has been practicing organic farming since 2020 to cope with the excessive use of water and chemical pesticides, used in conventional farming.

The turning point came when he realized that the use of chemical pesticides had not only become ineffective, but was reaching costs that were no longer sustainable.

Manghi Ram Majugarh decision to convert his 6 acres of land into organic orchards came up eight years ago, after he realised that the usage of chemicals had become ineffective against insects and pests. Thus he now makes use of natural and synergistic techniques and uses prepares natural compounds that act as pesticides and fertilizers, directly using the waste from his own crops, .

He explained to me that the use of natural pesticides that repel insects, rather than kill them, ensures that they do not develop forms of resistance, as is the case with chemical pesticides. Wandering around his land one can find dozens of different species of trees and plants, in contrast to most fields in Punjab, where wheat and rice are grown almost exclusively.

Wandering around the countryside in his district, it is still possible to find several families cultivating their land in a non-intensive way. In many cases the whole family is involved in farming, women, men and the elderly.

In most cases, however, cultivation involves the heavy use of chemicals.

Not infrequently, farmers use massive doses of fertilizers and pesticides, which become less and less effective as soils are depleted and pests and insects become more resistant.

Thus, farmers often go into debt to buy phytochemicals, without any advantage, as this does not lead to higher land yields. This practice causes many families to be in a dire economic situation and many marginal farmers to commit suicide.

Most of the land is planted only with rice and wheat, in a monoculture system, because of a government-guaranteed price system, the Minimum Supported Price, which is currently limited to only these two crops.

When the rice planting season begins, thousands of laborers can be seen in the fields, arriving from different parts of India. They are seasonal workers who are paid around 400 rupees a day (90 rupees is about one euro).

Surinder Pal Singh and his family own about 300 acres of land, 100 acres of which have always been dedicated to organic farming. He recounted that the organically farmed areas have always been unirrigated, but fed only through rainwater.

According to his story, the land they own was inherited from their ancestors, who, having arrived from neighboring Rajastan, bought it in 1853 from British colonists, who previously conquered it in 1839.

After the Green Revolution, which began in the 1960s, as early as 1975 his grandparents were trying to convince other small farmers to avoid the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, as they would be “like drugs”: soils would soon become dependent on chemicals and require increasing amounts of pesticides. But economic conditions and the need to provide regular harvests meant that only a portion of the land continued to be cultivated in a traditional, natural way.

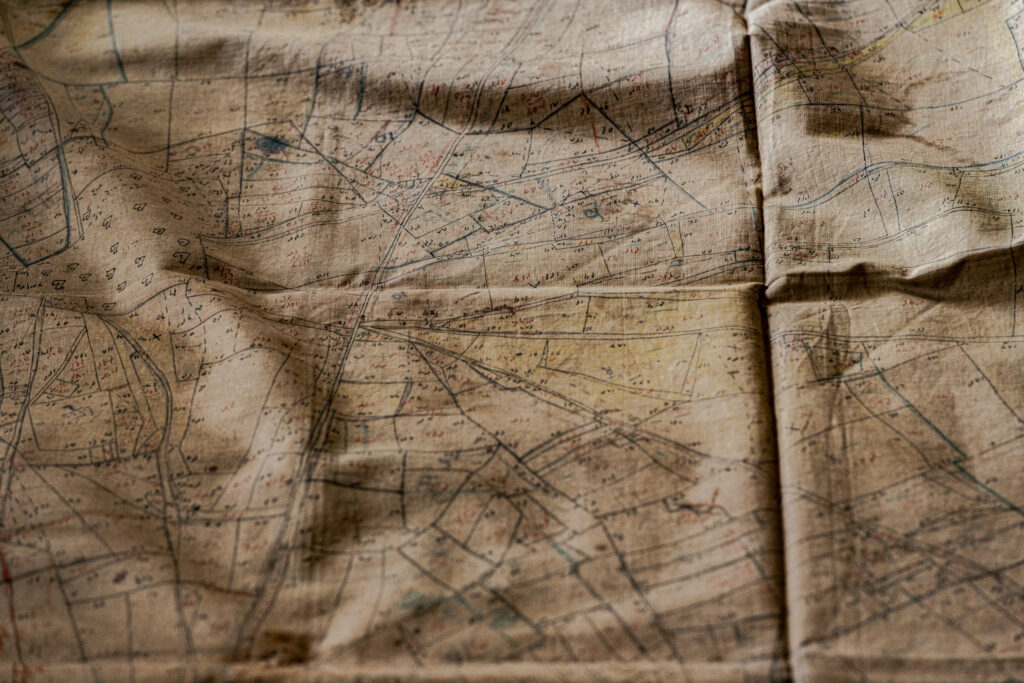

One morning Surinder showed old documents of his ancestors’ purchase of the land. These included a cadastral map of the town printed on fabric.

According to the recounts made by many of the farmers I interviewed and Umendra Dutt from KVM, in traditional Indian culture, the village was conceived as a system. Mahatma Gandhi, had theorized this even before independence: it was the Gram Swaraj. A self-sufficient organism in harmony with Nature, in which each person has a role revolving around agricultural activity.

Many of the farmers interviewed and Umendra Dutt of KVM often repeated to me that traditionally farming was not considered a job, but rather a way of life.

Even today in farming villages there are many artisans, including carpenters and potters, who produce the tools for land farming. In this system, labor was often remunerated in kind: artisans procured tools for farmers, who in turn provided them with grain and food after the harvest.

Also the relation between the families of landowners and laborers had the same mechanism, though in hierarchical structure: the bond between the families of laborers and workers and those of the landowners was thus inherited for generations. Today this system of ties is loosening, but in many cases, where the families of landowners and farmworkers and laborers maintain this bond, wages can be as low as 400 Indian rupees a day (around 4 euros), are compensated with additional supply of firewood, medicine when needed, and other forms of in-kind payments.

The permanence of some traditional practices is also evidenced by the presence, along the roads, of several sites for the production of charcoal for cooking, which caught my attention.

Charcoal is produced in hemispherical brick ovens, whose door is closed once completely filled with logs. The logs, due to the low amount of oxygen that enters the combustion chamber from the holes along the walls, burn for several days, very slowly. Incomplete combustion transforms the wood into charcoal.

I met Rupsi Gargi in Jaitu village. She is the KVM’s Trinjan project coordinator since 2018, when she started workig with the women of the village to recover ancient weaving techniques.

She explained to me that Punjab was originally a land were cotton was widely produced. The local Desi variant was the main crop, but it has been now replaced by the genetically modified Bt Cotton variant, initially brought to India by multinationals such as Monsanto and Mahyco in 2002. Despite that, today cotton has virtually disappeared in Punjab, replaced by rice.

Ruspi Garg explained to me that industrialization and the market economy have broken the links between farmers, artisans and processors that were traditionally present in the rural system. Thus, the aim of Trinjan project is the restoration of of traditional weaving techniques, through a weaving school, which now involves about 30 women. During our meeting and the visit at the weaving school, Rupsi Garg illustrated the multidimensional nature of the impact of the project: not only educational, but also cultural, as it aims at the recovery of traditional crops and handicrafts, and with a strong pontiality in empowering women by teaching a job and thus providing them a source of income.

Being a land where agriculture has a strong cultural and economical importance, and as the land had been long ago designated as the breadbasket of Indian Nation, political controversies play a crucial role in the history of Punjab. The protests of Punjabi farmers have been an important protagonist in the news reports in India for many years now.

My encounter with Punjabi protesters is reported in the article that I wrote for PagineEsteri: since February, farmers have been protesting with a permanent sit-in, to demand that the extension of the Minimum Support Price to 23 crops, a guaranteed price system, which according to them is a necessary measure to ensure greater diversification of crops, now limited to only rice and wheat.

The sit-in has been stuck since January at the gates of Haryana, at the Shambha Border. On Jan. 22 2024, clashes with police resulted in the death of a 22-year-old protester who was hit by a teargas shell.

Although the call to extend the guaranteed price system is a legitimate demand to protect farmers from market fluctuations and from large multinational corporations, that have disproportionate abilities to set prices at will, re-establishing a system that respects the laws of Nature while ensuring food security needs additional forms of intervention and scientific research, where food quality, health and ecology are the true “Permanent Center of Gravity” of society.